Yes, I know, it’s been a year since lesson 01. We have still been learning. Most of that time was spent working very hard on mkblv02, which unfortunately I can’t yet talk about in detail here: we are working for a large company and they’re still very much testing and tweaking before going live. That’s not to say the project itself didn’t follow the process. We were getting feedback and talking to customers within weeks of starting and have now found more corporate-friendly ways to conduct some of those activities.

Anyway, somewhere in the middle of all that we found time for mkblv03, Tracked and mkblv04, which I’ll talk about later, both of those projects were more-or-less complete a couple of months ago but have each been waiting on a couple of things to go live.

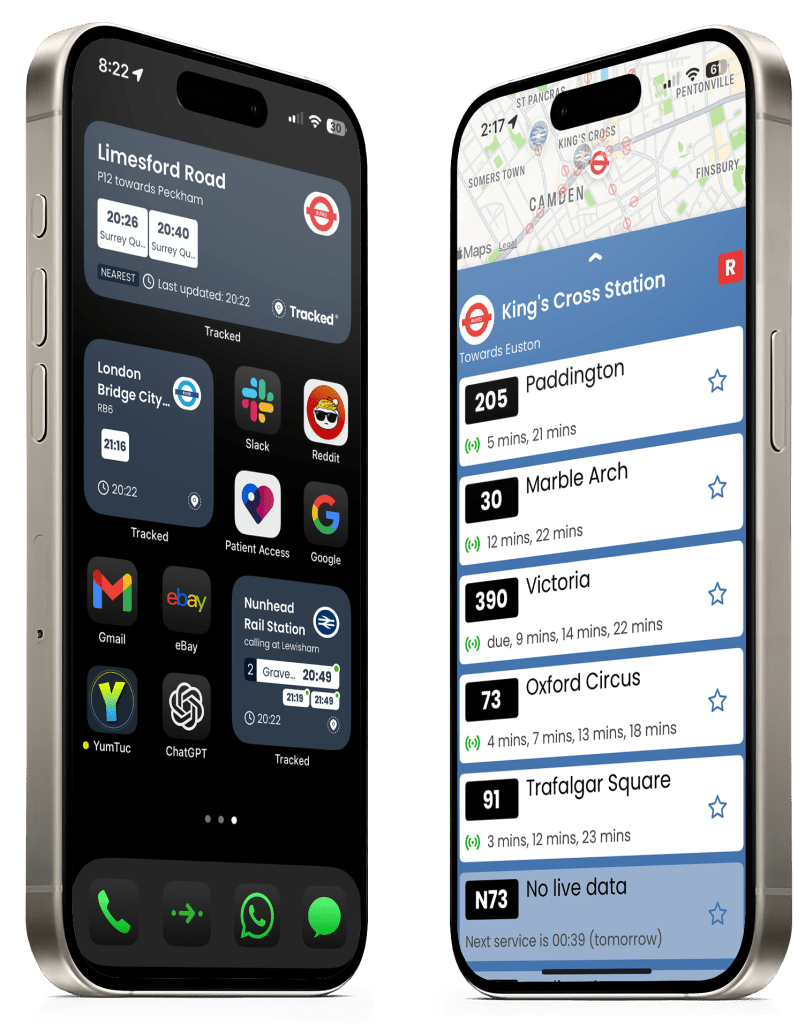

The idea behind Tracked really came from looking at what was available today in the app store if you want to plug yourself in to some of the most widely used public APIs in the UK. In particular, it was triggered by looking for apps that show National Rail data set, and those that show Transport for London (TFL) information.

Anyone who’s a regular train user (and particularly those that use short, frequent services) will know that the AppStore choice isn’t great. National Rail’s own app looks like it hasn’t been updated since the original iPhone, and is cranky as hell. Other apps suffer a more modern dilemma, the business model – either needing to flood the entire interface with affiliate ads, or pushing a subscription so hard that the it takes ages to get train information, which is of course what you’re there for in the first place.

Similarly the TFL API is typically shown in the context only of journey planning (think excellent apps like CityMapper or even the integration with native mapping tools).

Is there a gap in the market for an app which helps you track the things you regularly use and makes that information almost instantly available? In particular, we wanted to see if we could leverage the iOS widget infrastructure to show data right on the home page, not requiring the customer to even open the app, let alone navigate a million mini-banners or pick, for the 1,000 time that they don’t want a subscription today.

The app is live today:

Please do have a look and let us know your thoughts.

So what have we learned.

Again, we’ve been amazed by the speed and flexibility of the tooling and the generosity of the community. For those interested, the app is Expo, Express and Supabase. Our first prototype was showing data in the first week. A new Expo feature, continuous native code generation made the widget part of the project possible. But in truth, that would have been 1,000 times harder if it weren’t for pioneers showing their CNG examples to the whole community.

We’ve, of course, learned a lot about widgets too. It’s a remarkably constrained environment – both in terms of pure pixels (and therefore how you design) but more importantly, the operating system itself decides when the widget will be refreshed. Clearly this is less than ideal for a service which tracks buses and trains. But I think we’ve shown there is still a lot of value.

Could we have found out the technical stuff another way (other than doing it)? I don’t think so. Most of the breakthrough moments with understanding constraints happened when we were looking at a real device (often while commuting or travelling around London) to understand the frequency of updates and accuracy of data.

Similarly, until you’re looking at the API responses themselves, you don’t really know how the data will work, and you don’t really know how crazy (for example) bus times are. You can have a bus suddenly be 10 minutes late. The live times seem to have almost nothing to do with the schedule. Night busses often start at 3am (who knew!), tubes have IDs but DLRs don’t, buses know which direction they’re heading, but tubes don’t, Arsenal’s match disruptions are loaded into the system a season in advance, and on and on. Interesting perhaps, we learned that there was a major bug in the riverbus API and got TFL to fix it. Are we the first to really use river bus data in earnest?

Again without the community (and TFL hosts its own excellent community). I’m not sure how many of these things we would have gotten to grips with. Some thing are documented. Many aren’t, including TFL’s own somewhat whacky web socket integration.

So we learned technical stuff. Building the interface also quickly showed us what works and what doesn’t for finding routes, picking what you want to track, which disruptions you want to be notified of, which you want to be able to see and which are irrelevant and so on.

And then of course, just as we were in the final throes of publishing it, TFL was hit with a massive cyber incident. This has meant the tube API went down completely (and it is still down today) with many other APIs being limited. The TFL team is clearly working hard to fix it, but this does mean they aren’t fixing much else. For our part, we bit the bullet and made the app work without the relevant APIs because we wanted to launch and get feedback.

Will it work? I think the biggest test will be the financial dynamics of marketing it, and that is still in front of us. But, as per the ethos, we didn’t know whether it could be built, how it might work and whether it would be useful. And now we know those things.